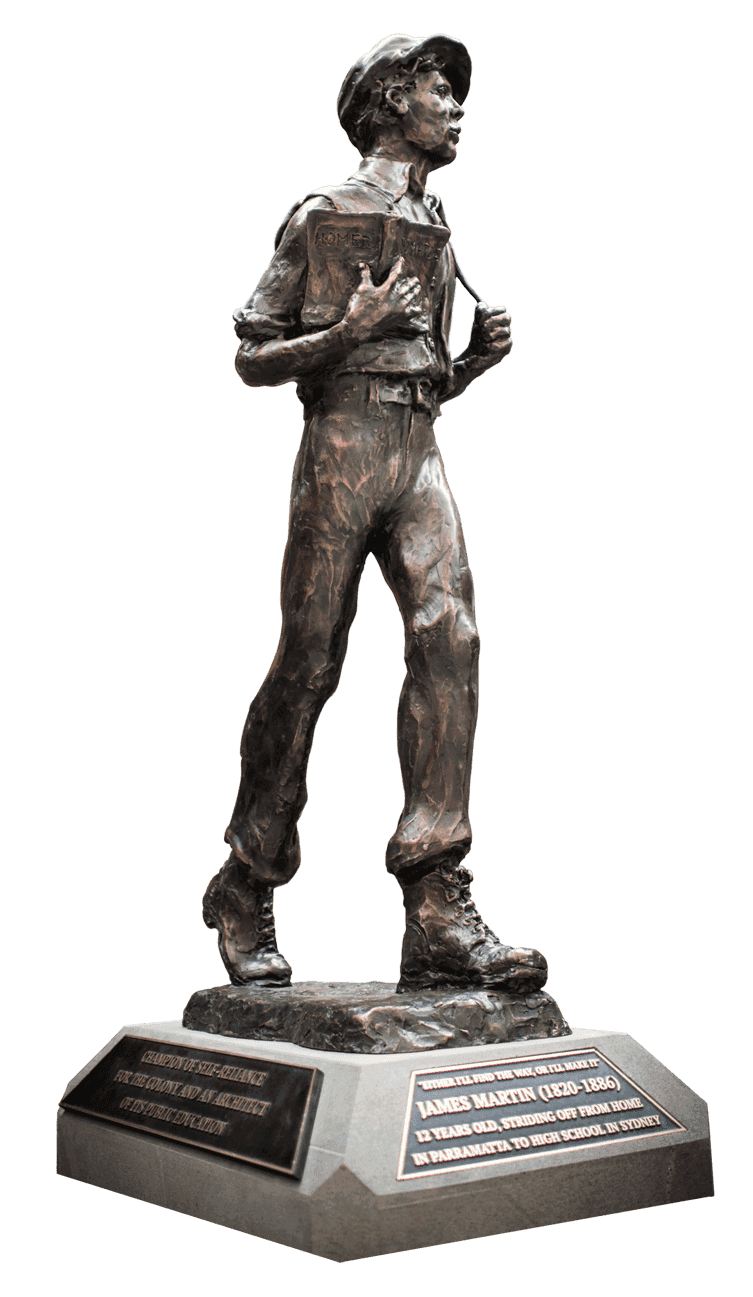

Martin’s life motto was: ‘Either I’ll find the way, or I’ll make it’

He went to Sydney Grammar, and there he was a star. He learned about those noble ideas of democracy, the rule of law, philosophy, science, and harmony and beauty. He loved the classics.

At eighteen, he went into journalism, and by his early twenties he was a feared editor. It was not enough. He went into the law, and by his late thirties he had become a highly successful jurist. It was still not enough. He went into politics, and became Attorney-General, and Premier of New South Wales. He ended his career, and his life, as Chief Justice, the only person to have accomplished all that in the history of the state.

Martin was a passionate advocate for self-reliance for the colony; an architect of Australia’s first public education system; the instigator of many schemes to educate street urchins; and a mentor to Henry Parkes, the father of Federation.

A triumphant, and almost completely forgotten, life.

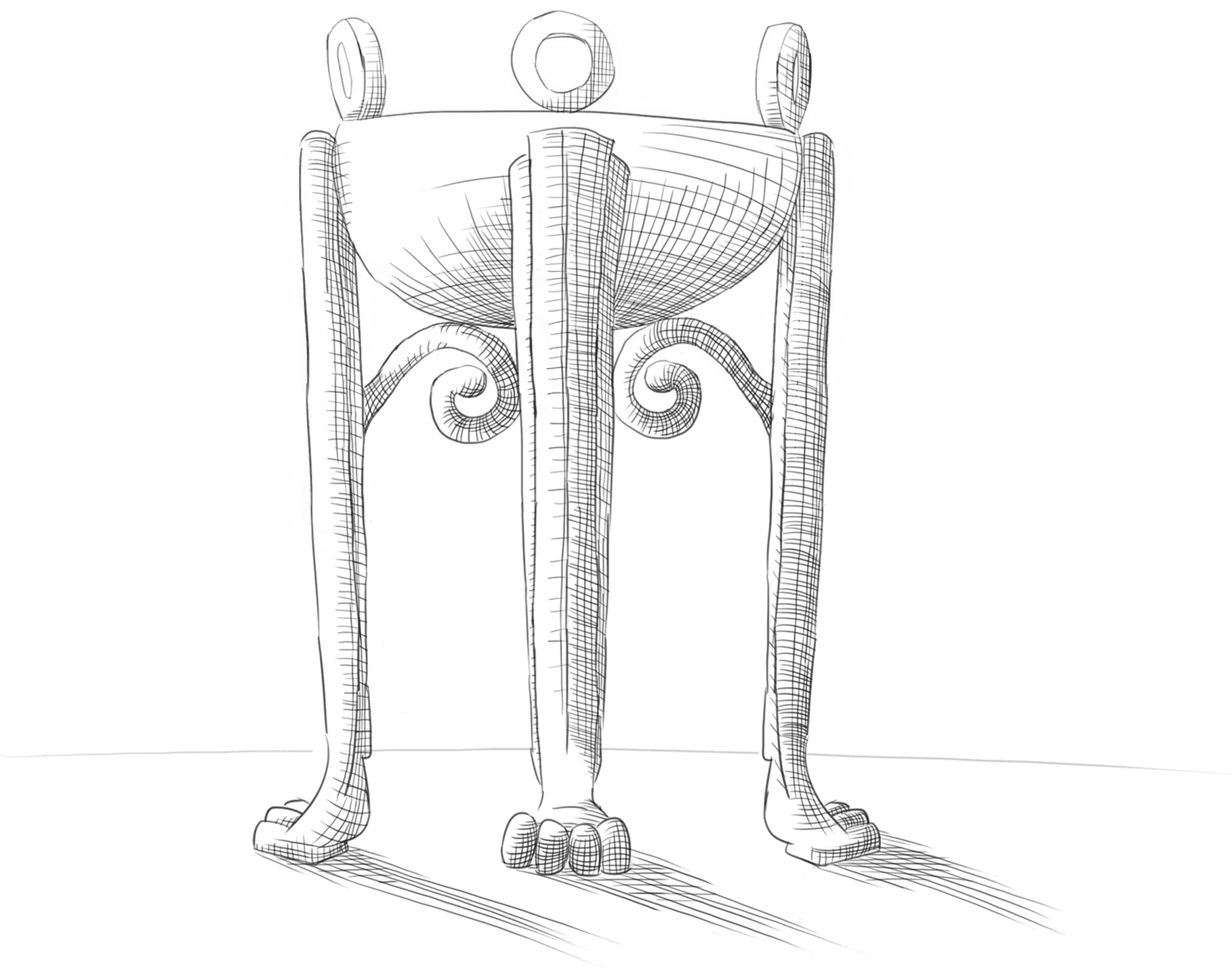

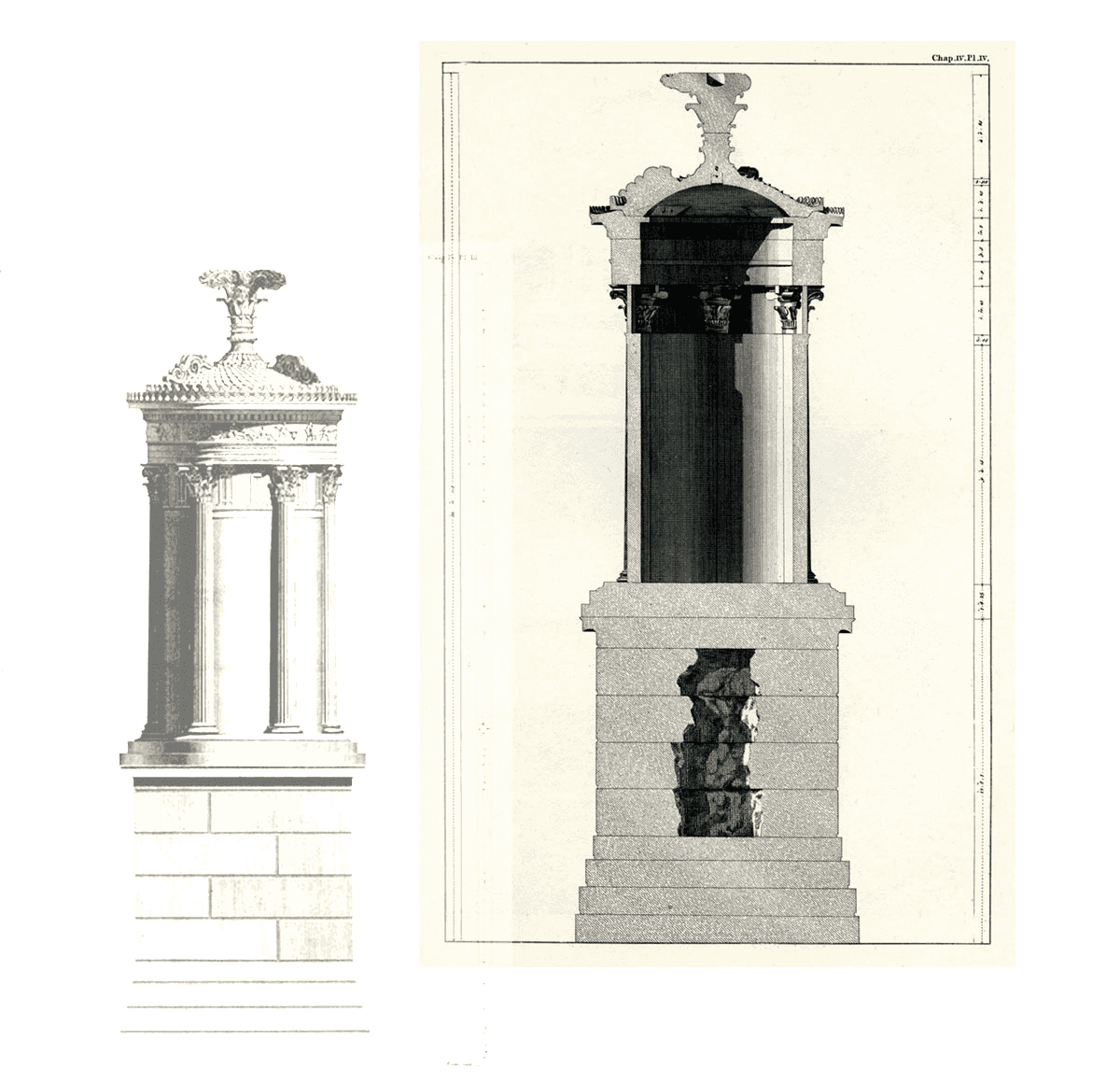

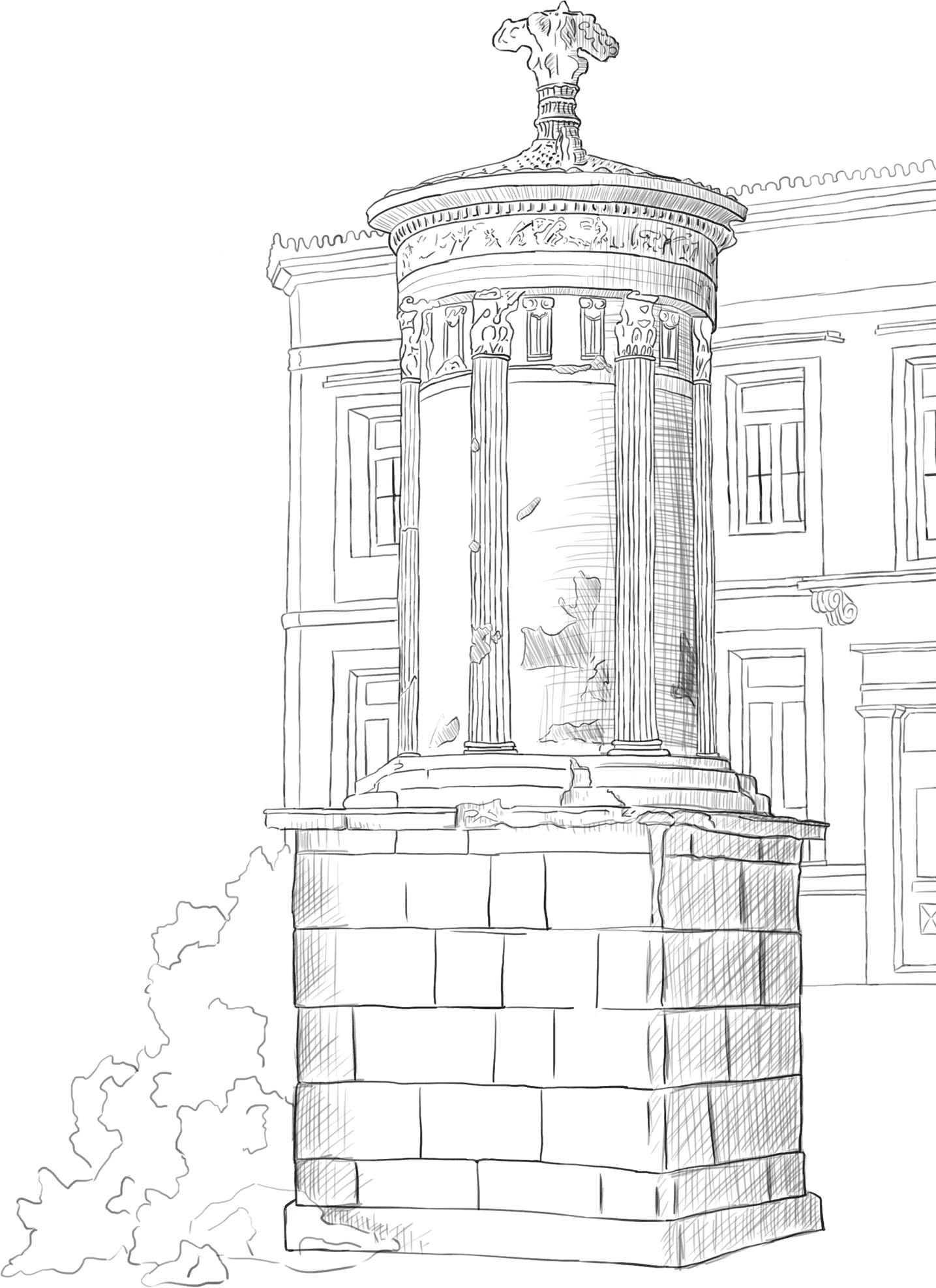

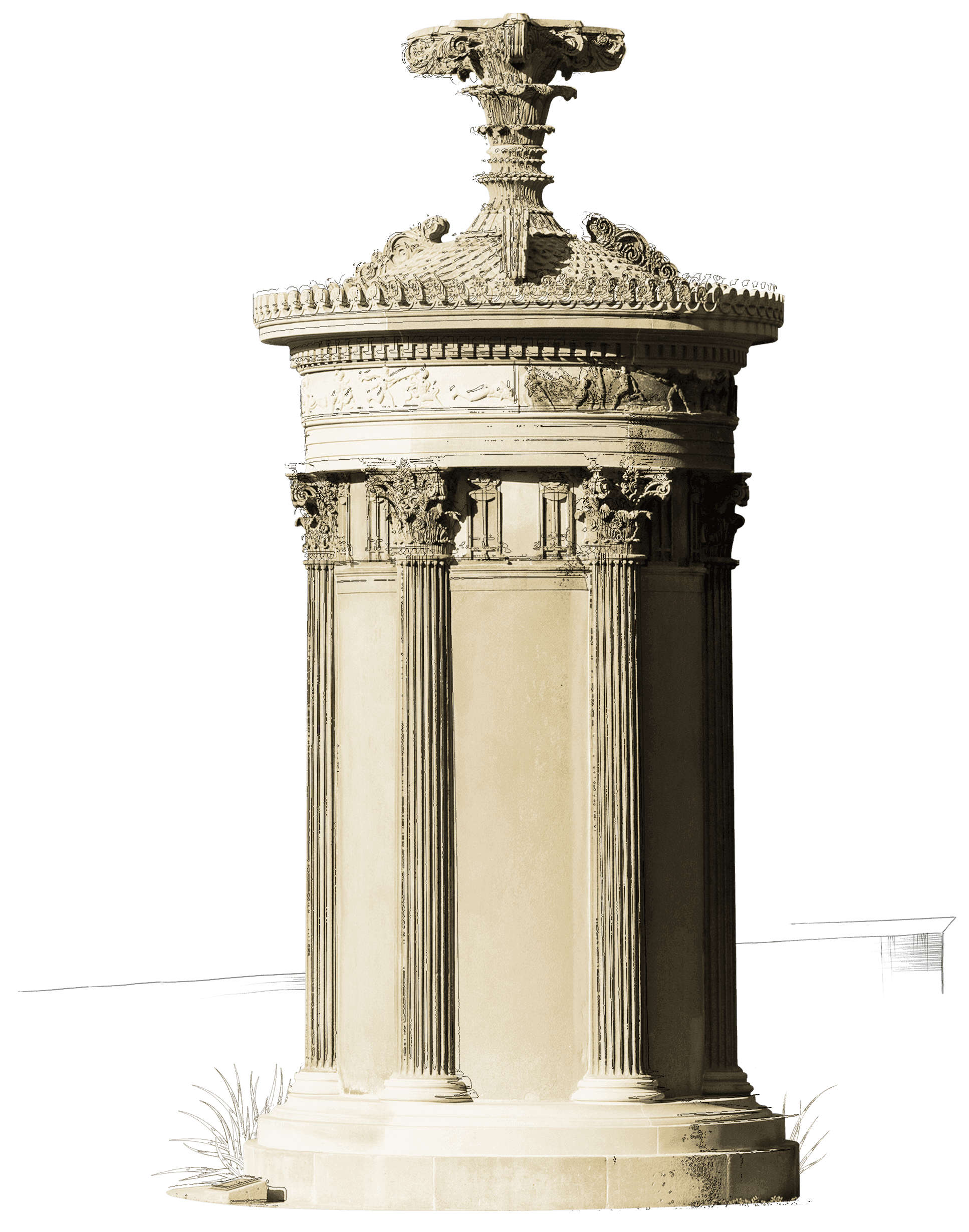

In 1868, while he was living in “Clarens” in Potts Point, Martin commissioned, and paid for, our glorious sandstone copy of the monument that the wealthy choregos Lysicrates had built to celebrate his win in 334 BC. Just as the ancient marble one had embodied the great classical ideas, so did the sandstone replica express them for the new southern land. And just as the ideas actualised in the monument made Martin, so did Martin make the monument.